Peace and industry.

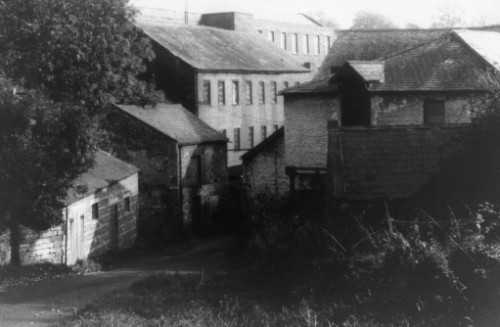

As it was at Cummersdale Mills, on the right the Corn mill behind the more modern garage. On the left a stable, relatively modern, a smithy shop behind it, and the two old cotton mill buildings which later became part of Stead McAlpins hand block printing departments.

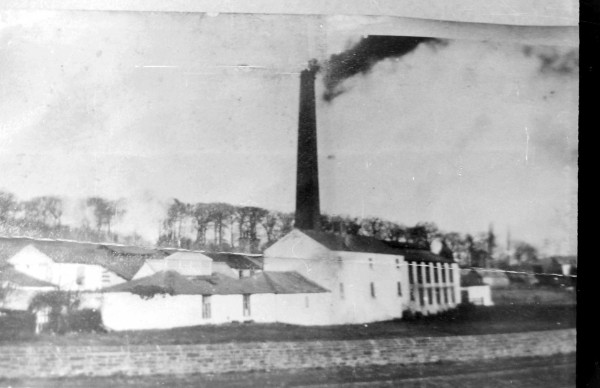

The Dye-Works

Joining the corn mill at Cummersdale mills in the 1780's was a Dye house owned by the Fergusons. It was situated on land between the bottom village houses and Cummersdale railway station. It is well established that Richard Ferguson (1716 - 1787), a check manufacturer of Carlisle is credited with being one of the City's textile manufacturing pioneers, and that his sons, John, Richard and George, continued to expanded his business. At Langthwaite Mill, Warwick Bridge, they were spinning cotton before 1790. As early as 1781, John Ferguson had leased fields at Cummersdale. The two fields were Watery Holme and High Stone Beds, which were divided by the mill stream that had for many years powered the Corn Mill further downstream, they also leased fields further up stream which the mill stream ran through. By 1788, John had been joined by his brothers, Richard and George. By this date they had erected on the leased land, buildings for the purpose of bleaching and manufacturing of cotton. By 1801 the Fergusons had purchased the lands they had originally leased and built on. John Ferguson died in 1801, Richard in 1811, and George in 1820, and the business passed to other branches of the family, including their cousins, the Dixons, but the business finally returned to John's two sons, Joseph and George, who carried on the business under the name of J.R. & J Ferguson

In 1839 a severe storm with hurricane winds caused considerable damage to the properties, their 100 foot chimney at their bleaching and dyeing works was a victim. Two thirds of the chimney was blown down on to the buildings below. By sheer luck no one was injured, but the buildings were extensively damaged. However, production was carried on.

In 1849, the Fergusons decided to retire from business, and in an advertisement in the Carlisle Patriot the woks were to let. this advertisement gives an insight into the size of the works and its contents.

" The Works had a never failing stream of water running through the premises (held in the highest estimation for dyeing and bleaching) and skirted by the Maryport and Carlisle railway, by which coals may be supplied. The premises contained a large blue dyehouse, containing 50 cast iron vats, 4ft X 6ft; A fancy dyehouse, with a large copper and yarn boiler; a bleace house; a water wheel; a pump and large cistern for supplying the buidings with water. The buildings consisted of stove and drying houses, open sheds, yarn rooms, warehouses, stables, two dwelling houses for the manager and foreman, plus other buildings. The whole of the works is enclosed by a wall and gates."

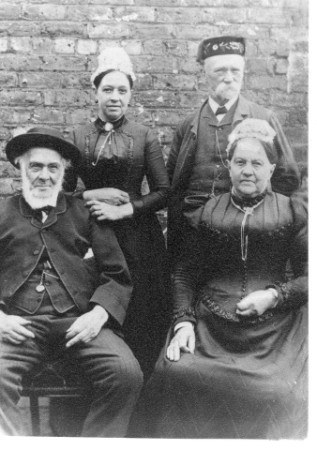

The company that leased the works after Fergusons retired was Lowthian and Parker, later to become Lowthian & Fairlie. This company carried on their dyeing business at the Cummersdale works until 1882. Their manager and head dyer, William Scott, was quite famous in the dyeing trade. He was originally from Caldbeck where he worked in his fathers small dye-works. He left there when he was a young man to start employment with J.R. & J Ferguson at Cummersdale dye-works. His abilities were soon recognised and he was promoted to foreman and soon afterwards manager. Mr Scott played an important part in the development of Perkin's coal tar dyes. In Scott's obituary in 1894, we learn through Lowthian & Fairlie's London agent, Joseph Pattinson, (a native of Wigton), that W.H.Perkin, the discoverer of coal tar dyes in 1856, made a link with William Scott. Perkin had been experiencing difficulties initially in getting his invention accepted, and had mentioned this to Joseph Pattinson. Pattinson recommended Perkin to visit his friend at Cummersdale, William Scott. As a result, Scott had the honour of being the first to apply these colours to the dyeing of cotton yarns. This fact was confirmed at a lecture on coal tar dyes given to the Carlisle Scientific Society in April 1883, published in the Carlisle Patriot.

Lothian & Fairlie carried on their business at Cummersdale works until 1882. The works were then leased to another Carlisle company, the Mains Manufacturing company.After three years the works were let again to Mr James Mungall , who also had a dyeing business at Warwick Bridge. Mr Mungall continued his dyeing business at Cummersdale until 1901, when Stead McAlpin purchased the properties from the original owners, the Ferguson's.

After Stead McAlpin purchased the works, a group of local businessmen decided to rent the works in 1901, and they set-up a company known as the Cummersdale Dyeworks Limited. They intended to take over the business which had been run by James Mungall and his sons. Among the seven shareholders in the new company were Joseph Amos, John Harris Dobinson and William Hurst, all managers at Stead McAlpin print works, and Frederic Bailly, the cotton mill manager. Robert Scaife, a coal agent , Joseph Edgar, a gentleman, and Robert Briggs, a manufacturer, were the other shareholders. The new company lasted eight years, and in November 1911 all the employees engagements were terminated and the company ceased trading. The premises revered to Stead McApin who used the buildings for storage of machinery ,etc. Fire seriously damaged the buildings and in the 1970's they were finally demolished.

The Dye-House managers house in the yard behind the main building

The Dye-works at Cummersdale Mills c1900, managers house behind main buildings.

Mr William Scott,(seated) the Head Dyer with his wife, his

daughter and son in-law standing behind.

The Cotton mills.

In 1992 the building known as the block printing factory was demolished. It stood on land at the bottom of the hill road on the left hand side. At one time there was another smaller building attached to it. Both of these buildings were originally built as Cotton Mills, the buildings can be seen on the photograph at the top of this page. The smaller building was built in the 1780s. It was Forsters, the carlisle bankers, and manufacturers that built and started the cotton spinning mill at Cummersdale. They built their mill opposite the Corn Mill using the same mill stream to power their machinery. This early mill was built of brick with a slated roof and was three storeys high. In these were three spinning rooms, and a carding room, each 69ft X 30ft, and two spinning rooms and a reeling room, each 41ft X 16ft broad.. With store rooms, offices etc. Also attached to the building were joiners and blacksmiths shops, (see photo at top). The machinery was driven by a large water wheel with a 14 foot fall. The mill contained beteen five and six thousand spindles. Also built at the same time were a managers house and workers cottages. Forsters had been quick to spot a good business opportunity, as there was at the time an increased demand for the spun cotton due to the growth of calico printing in and around Carlisle and the advances in weaving technology. Forsters continued cotton spinning themselves until about 1830, when they let the premises to J. R. & J Fergusons, who already owned the Dyeing Works at Cummersdale. The Ferguson's continued the cotton spinning until they retired in 1848, but during this time the ownership of the mill changed. In 1837, Forsters were declared bankrupt, and the cotton mill, the corn mill along with many other of properties, were auctioned. Both Mills were bought by Daltons, who at the time were tenants of the corn mill. After the Fergusons retirement the cotton mill was advertised to let, but apparently there were no suitable applicants, as Daltons eventually took on the cotton spinning business themselves. Obviously business boomed for in 1854, they had a new bigger cotton spinning mill built along side and adjoining the old mill. The four - storey building was not completed without mishap, however. It is recorded that two labourers were filling gaps in the arched roof of the prospective engine house., and directly beneath them , on a lower arch, Mr Robert Dalton was standing speacking to another workman. Suddenly the keystone on the upper arch gave way and the stone and men fell onto Mr Dalton and his companion underneath. The combined weight was too much for the lower arch, which also gave way, and the four men fell to the ground and were buried in the rubble. Fortunately, although all the men were injured, they all made full recovery, and at the end of October 1854 the new mill was finally opened. It was a great occasion, involving tea for 70 ladies in the afternoon and supper for 100 men in the evening, with dancing until midnight. Six years after the new building opened international events had a drastic effect on the business. At the beginning of the Civil War in America the Southern states were blockaded, thus preventing raw cotton from reaching England. This cotton famine in 1860, quickly began to effect the cotton mills in the country. At first the mills were put on four days a week, but within a short time the working week was down to two days, and shortly afterwards the mills closed altogether. Many families were hard hit by these events. A relief committee was set-up in Carlisle, and they started sewig schools to occupy the unemployed mill girls, and to provide clothing for the families. Twenty five of the Cummersdale mill girls went to the sewing school in Caldewgate, but it was suggested that owing to the inclement weather and the distance the girls had to walk, it would be a good idea if a sewing school could be set-up in Cummersdale. An anonymous lady donated a pair of woolen stockings to each one, and Stead McAlpin supplied fabric off-cuts to the school. When eventually, with the end of the American Civil War , cotton befan to arrive in England again, it is said that the whole village turned out to cheer as the first bales passed through on their to the mill.

In the Carlisle Journal 1903, the following notice appeared:

Cummersdale cotton mill to close

The firm of John Dalton and son, cotton manufacturers, have decided to stop their mill at Cummersdale in consequence of the unsatisfactory state of trade. The work people, 150, mostly women, are now working their notice. The mill will be closed for good in a fortnight's time. The stock of yarn will be kept until they find a market for it.

Pattinson Dalton, son of the late John Dalton, was manager of the business. He had been advised in his fathers will to sell- up both the cotton spinning and the corn milling businesses. When, a little later, he came to sell the cotton mill, he placed an advertisement in the Carlisle Journal. The auctioneers were Hugh Shaw and sons of Oldham. No doubt the same advert would be in the Lancashire and Yorkshire papers also. The advertisment lists that it is an important sale of 21,316 mule spinndles, a big increase on the five thousand spinndles advertised in 1837. The advert gives an insight into the ancillary equipment used in cotton mills. After the sale of the equipment, the mill buildings, along with the corn mill and the 39 terraced houses, mill house and the two previous manager's houses were for sale. Pattinson Dalton's financial adviser had calculated that the properties were worth at least £10,000, but the price asked for was £12,000. Mr Edmund Stead paid £10,000 for the properties in 1905.

The cotton mill and corn mill buildings were converted to be used for the company's hand block printing department. Their hand block department was spread out all over the print-works. The large cotton mill building was fit - out on each floor with 12 yard long tables for hand block printing. The smaller, earlier cotton mill building that was attached to the larger one, was used for storing the large collection of wooden printing blocks. At this time hand block printing was at its zenith with over a hundred block printers being employed by the firm. The corn mill building which was bought at the same time, was, after a few years also used to house hand printing blocks. Hand block printing at the print-works ended in 1978, and soon afterwards the smaller earlier mill building was demolished along with the corn mill building on the opposite side of the road. The bigger cotton mill building that had been the block printing factory was emptied of its 12 yard tables and converted for use as a cloth store. It remained as a store until 1991 when the building was demolished. Around the mill buildings were several single storey buildings, including a cottage and an old mill school. One of the buildings was the boiler house which had supplied heating and, in the latter days of the cotton spinning, power to the machinery. This building, along with the adjoining cottage, was demolished in 1990. The school building, which housed the joiners' shop from about the 1920s, began its life as a school for the mill children, but was still used as a school until about 1914.

The cotton mill or later the Block printing factory, the small single storey building was originally the wash house and toilet block for the bottom village. .

Inside the mill showing the light airy floors ideal for initially cotton spinning and latterly hand block printing.

The building prior to demolition

Cummersdale Print-Works

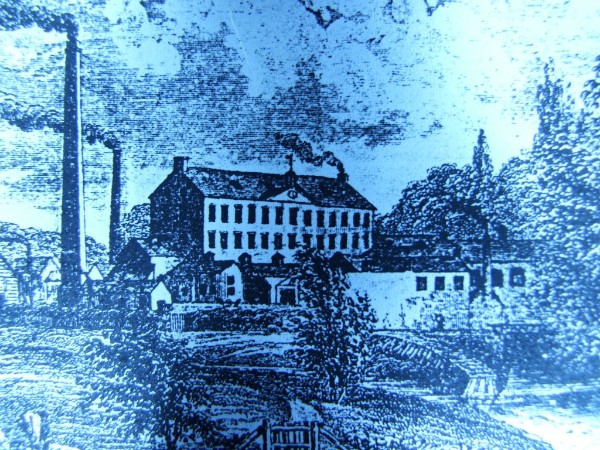

In 1801, Forsters, the Carlisle bankers and manufacturers who already owned the cotton spinning mill and Corn mill at Cummersdale, decided to build a Print-works, using the existing mill stream for power and water for processing. In May of 1801, the Carlisle Journal reported that the foundations of a workshop had been laid; the dimensions of which are ninety yards by forty. It was just six years earlier that Hutchinson in his history of Cumberland and Westmorland referred to over 1,000 people working in the printfields around Carlisle, at a time when the population was only 12,000. It was against this background that Forsters decided to built a Print-works. The company was named Forster, James & company, later changing to Forster, James,Wastell and Donald, the new company printed for the apparel trade.

Although the company had a good reputation for quality of their goods the company ceased trading in 1817. The buildings stood idle for 17 years and an advertisement for the letting of the works appeared in the Carlisle Journal in 1823. The company were using engraved copper roller printing, hand block printing and engraved copper plate printing. They also had a blue dye-house and a dye -house. It was'nt until 1835 that the works were again set in motion when Thomas McAlpin and his relatives rented the works and moved from Wigton.

Thomas McAlpin had been a principal partner at the Wigton Stampery, where his partners had been Richard and Anthony Halliley. The latest evidence suggests that the partners had a fall - out, and Thomas with his brother Duncan, their nephew, Hugh McAlpin and Thomas's step son, John Stead, moved to Cummersdale and founded the present company.

The new company started with two styles of printing,; the ancient craft of hand block printing and the then, more modern engraved copper roller printing. These two styles of printing were followed shortly afterwards by wooden surface roller printing.

The print-works from a letter heading of 1847, this is a similar view of the works as Sam Boughs painting, 1844.

It was'nt until much later that any advances were made in printing styles, when screen printing was introduced at Cummersdale print-works in 1930.

Although printing was mainly for the furnishing trade, the company also printed dress fabrics, quilts, bedspreads, tablecloths, window blinds, shirtings and linings. Natural dyes and mordants were used to achieve the diffent colours and shades.

Farming was also part of the company economy and the early stock books have many entries of the farming stock, ploughing equipment, milking and hay making equipment, along with hay in the loft, potatoes and turnips. Until 1843, the works were just rented, but because Forsters, the owners were declared bankrupt, the works were offered for sale. Thomas McAlpin and his relatives purchased the works in 1844 for £2,500. In the first year of trading the company were trading in every area of Britain and within a few years they were trading in South America. John Stead and his brother in law, Captain Thomas Christian, bought a Brig sailing ship named "Mary" which with Thomas Christian as it's captain carried goods around the coutries of South America between the years of 1838 - 42.

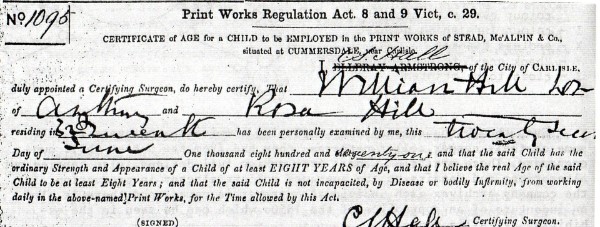

The certificate for William Hill, son of Anthony and Rosa Hill of 32 Queen Street, Carlisle in 1871.

A school existed at the works for the education of the children who worked there and a certificate had to be completed by a Surgeon, the certificate gave the name

of each child and its parents name and address. The child had to be at least 8 years old. The schoolmistress at the works in 1846 was Mary Ann Nichol, who was paid seven shillings a week. The children worked in the mill for nine hours, and then had two hours schooling. The school consisted mainly of religious education and the stock of the school room included bibles,slates, etc. It was the printers who paid for the childrens education not the company!

By 1860, Cummersdale was the only print-works left in Cumberland, by 1886, a Paris office was opened, and by 1892, an agency was opened in North America.

Stead McAlpin block printing factory about 1910, previously a cotton mill.

Because of the length of time the print-works has existed, it had obvious effects on the village. A small number of houses belonged to the works from the outset, but a big change came in 1905, when Mr Edmund Stead, bought the recently closed cotton mills, the corn mill building and the disused dye-works along with the two rows of back-to-back houses. Just over twenty later the company built many houses in the top village for their workers, they also at one time supplied water and electric lighting to the village.

Edmund Stead, who inherited the works from his father, Edmund lived at Dalston Hall from 1894 until his death in 1934 and gradually purchased most of the land in the parish and over the river on the Blackwell/Durdar side. The cotton mill building which was four storeys high was converted into the company's hand block printing departments and the smaller mill building and the corn mill building were used to store the wooden hand printing blocks, of which there were thousands.

In 1924Stead McAlpin became a private limited company with Edmund Stead as the Governing Director. Hand block printing and engraved copper roller printing had continued, but in 1930 a new style of printing was introduced to compliment the older styles; this was hand screen printing. Two new buildings were erected for this, one before the Second World War and one after. The buildings housed several 60 yard tables for the screen printing operations. The war drastically interruped everything in 1939 as printing for the home market was restricted, but exports were still allowed and most of the works were used for war work. Repairing bullet - ridden fuel tanks from aircraft and sorting rivets into various sizes were a couple of the jobs undertaken for war work. And of course most of the men at the works were called up on National Service, leaving the works short of workers. These vacancies were filled by women workers, and even block printing, the highest of the trades, was carried out by women.

In 1934, Edmund Stead died and Gilbert Stead, his son, ran the company for a number of years, but because of conflicting interests, the works were eventually run by the late Edmund Stead's son-in-law, Mr Peter Diggle, who continued as General Manager until 1957, when he relinquished the position to his son, Ronald Diggle, although he retained his position as Chairman of the board. When Mr Ronald Diggle retired in 1980 it ended the Stead family connection with the company after 145 years.

Hand block printing at the works continued until March 1978, and the engraved copper roller printing finished a few years earlier. By this time screen printing had progressed from the hand screen printing, to semi- automatic, to fully automatic flat bed screen printing in 1961, and then joined by rotary screen printing in 1971. It is these two styles that continue to be used today. Digital printing is also now being used by the company. The company also carry out dyeing of fabrics as well.

In 1965, the John Lewis Partnership purchased Stead McAlpin outright. This protected the company from any hostile takeover by the big textile giants of the time. The Partnership ran the company until 2007, when they sold the print-works to Apex Textiles, a Manchester based company. The ownership of the design archive department was retained by the John Lewis Partnership, and is still situated within the works at Cummersdale. Apex, failed in 2009 and the print-works were bought by Christopher Soper, the company are now very sucessful and expanding their products and ranges. The firms name is still Stead McAlpin and Company.

Block printer (late John Blaylock) and tierer.

Harry Nicholson,(left) Sid Graham and Willy Norman (soss) extreme right.

The works from across the river

The modern works

The Railway and its Station.

The Maryport to Carlisle railway was originally built to service the coal fields of North Cumberland. The route of the line was originally surveyed by the famous railway engineer George Stephenson in 1836. The first part of the line, from Maryport to Arkleby, was opened in 1840 and was seven miles long. Work on the second part of the line was at the opposite end, linking Carlisle with Wigton, and this section of the line was finished in 1843. The land at Cummersdale Mills required for the railway to pass through on its way to Maryport was owned by J. R.& J. Ferguson who owned the nearby dyeworks. The line was opened on the 10th May of that year and the Carlisle Journal covered the event. It was a momentous occasion; at 12 o'clock all the shops in Wigton closed and crowds gathered near the temporary station near the windmill on the north side of the town. This was as far as the rails went at this date. During the early afternoon three trains of carriages arrived from Carlisle, drawn by the "Star", which was the new patent engine of Hawthorne and company of Newcastle. Also lent for the occasion were the "Ballantine" and the "Nelson" engines which belonged to the Newcastle and Carlisle railway.

Soon after 1 o'clock the trains were filled with passengers. The Wigton band were placed in the first carriage, and at twenty-three minutes past 1 o'clock, with the band playing God save the Queen, the first train set off on its journey to Carlisle. The two other trains set off after suitable intervals between each one. The Journal continues to give great detail of the journey. "As the train got nearer Carlisle it crossed the Dalston Hall Holme, a distance of 5 furlongs, and at this point a good view is obtained of Dalston Hall and the Vale of Caldew, one of the most beautiful in the county, stretches away before you, with its smiling meadows and richly wooded eminences. "

"An embankment at Brow Nelson, 22 furlongs in length, and about 10 feet in height, and a short cut of about one furlong and forty feet depth, brings us to a bridge across the Caldew, opposite to Cummersdale Mills where the train was welcomed by the loyal miller, by firing of a gun." The Journal continues the detail of the trains journey to Carlisle. In the report it goes on to say that "the stations, which will be built of stone, will be at Carlisle, in Crown Street, Botchergate (it is expected), at Cummersdale, Dalston, Curthwaite, Crofton and at Wigton, near the windmill on the north side of the town."

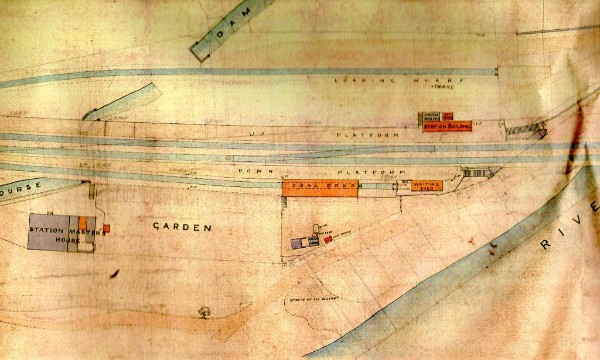

The promise of a stone built station building at Cummersdale was never fulfilled, as all the platform buildings were of wood. It is thought that the station was'nt opened until 1858 or later. At some point a Station Masters house was built of sandstone, between the railway and the river Caldew. The Cummersdale station was restricted in use for passengers until 1880, and even on the timetable the name only appeared as a footnote: "a stop at Cummersdale on Saturdays"! By 1887 there were six trains on weekdays and two on Sundays, and on Saturday an extra train stopped at Cummersdale. It was a single line until 1860, and trains had to wait in sidings until the on-comimg train had passed. The line was doubled between Carlisle and Dalston in 1860, it's thought that the station was built when they doubled the line, however, I know from a report in the Carlisle Journal in 1862 that the Cumberland Volunteers had chosen Cummersdale Mills for their rifle range and in the report of the first competition shoot, the Maryport and Carlisle Railway Company agreed to put the Volunteers down at the spot. This convinces me that no station existed at this date.

On the 1865 O S map of Cummersdale Mills there is a coal depot and siding, but no station or goods yard is recorded. Six years later the 1871 census records that John Barnes, who lived at Cummersdale Mills village, was a stationmaster and coal agent. By 1881, Robert Scaife had become stationmaster and coal agent. This lasted until his death in 1908, when the position was filled by George Scurr until about 1920.

A new waiting shed was built at Cummersdale station in 1885, and five years later the down platform was rebuilt and lengthend. This alteration was carried out to accomodate the larger number of passengers who attended the Carlisle race meetings. At the shareholder's meeting in 1885 it was stated that nearly 4,000 people had been carried to Cummersdale and back again over the last two days of racing.

The station in decline

Its difficult to imagine that 60 years ago Cummersdale station was a busy passenger and goods terminal with a coal drop siding and coal depot for distribution, a weighing facility at the river side of the station and a goods yard with an unloading wharp and crane at the other side. On the station itself there were well looked after buildings and gardens all along the platforms. It must be remembered that at Cummersdale there was no bus service until 1924, so the railway was an important means of transport into Carlisle.

In 1923, the Maryport and Carlisle Railway Company was amalgamated with the London, Midland and Scottish Railway Company (LMS). The station was finally closed to passenger traffic in 1951, and goods traffic continued for a further ten years, closing in 1961. Stead McAlpin Print-works made an arrangement with British Railways whereby workers from Wigton and Aspatria could be dropped off in the morning and picked up again at night. A temporary stationmaster was appointed from the works to collect the tickets and put out the lights and shut the gates. This lasted for about four years.

Cummersdale Station plan 1903